- Home

- Nicole Kelby

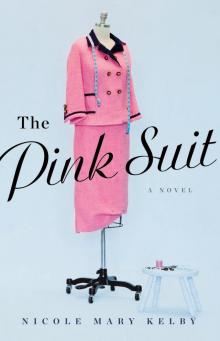

The Pink Suit: A Novel

The Pink Suit: A Novel Read online

Begin Reading

Table of Contents

Newsletters

Copyright Page

In accordance with the U.S. Copyright Act of 1976, the scanning, uploading, and electronic sharing of any part of this book without the permission of the publisher constitute unlawful piracy and theft of the author’s intellectual property. If you would like to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), prior written permission must be obtained by contacting the publisher at [email protected]. Thank you for your support of the author’s rights.

For those of us who fell under her spell

Introduction

“What a strange power there is in clothing.”

—Isaac Bashevis Singer

November 1963

There was that odd thing where he seemed to tilt to one side as if to whisper something to her, as lovers often do. Her head turned, the perfect hat still in place, and she, out of instinct, leaned in as if for a kiss.

His face softened.

It took a moment for her to understand.

It was then that something—gray, dark—tumbled down the back of the limo. She pushed him away and followed after it. Held it in her hands as if it were a broken wing.

The film shows this: the agent jumped onto the 1961 Lincoln and pulled her back into the seat. Unseen are the thirty-six long-stem red roses tumbling to the floor and the agent pushing her on top of her husband and then covering them both with his own body.

Heartbeat upon heartbeat. Then silence.

“Oh, no,” she whispered.

It was not a wing at all.

In the chaos of the moment, the agent focused on the suit. He knew she was crushed beneath his weight. He couldn’t help that. He knew her face was pressed into her husband’s. He couldn’t think about that. But he could focus on the pink beneath his body.

She was so quiet. He expected her to scream, but she didn’t.

Beautiful suit, he would later write in his memoirs.

Most who can recall that day in Dallas think of the film’s grainy black-and-white footage. Those who were there remember the suit.

That morning, an entire ballroom awaited her arrival. The President joked about her being late, but she wasn’t late at all. The advance man knew that the Wife was to make an entrance that would not be easily forgotten. The band played “The Eyes of Texas Are Upon You.”

When she finally walked into the ballroom, every head turned to watch her take the stage. The applause was thunderous. Even her husband took to his feet, laughing. “Nobody wonders what Lyndon and I wear.”

The suit was his favorite. She wore it often. “You look ravishing in it,” he told her. Asked her to wear it that day.

She was “lovely in a pink suit,” an advance man would later tell the reporters. Even Lyndon smiled at the sight of her.

When it was all over, in the underground parking garage of the hospital, Lady Bird would glance over her shoulder for one last look at the President. His limo was sideways, as if abandoned. The doors were flung open. The agents were desperate to get him inside: some hovered over the dark-blue Lincoln, pleading with the Wife, who lay across her husband’s body, refusing to move. Some stood with their backs to it all, their guns drawn.

There were no doctors or nurses; there was really no need.

In the midst of it all, Lady Bird remembered seeing “a bundle of pink, just like a drift of blossoms, lying across the backseat.” It was that immaculate woman, in that beautiful suit, covering her husband’s body.

Aboard Air Force One, ninety-nine minutes after it all began, LBJ stood with his hand on the Bible. The widow stood next to him, still in the pink suit. The photographer posed her so that only a small stain on her sleeve could be clearly seen. Lady Bird tried to persuade her to change; the maid laid out a white dress.

“Very kind of you,” the Wife said, but would only wash her face, which she later regretted. “Let them see what they have done.”

The photos ran in black and white; nothing could be seen.

At five a.m. on November 23, twenty hours after the Wife met her husband in the ballroom—and after his body had been delivered to the Bethesda Naval Hospital for the autopsy—she returned to their private quarters for the last time. Twenty hours. One thousand, one hundred and eighteen miles. Wife to widow.

Finally, she removed the suit.

While she was in her bath, it was taken away. Some say that the maid put it in a brown paper bag, which may have been hidden in the Map Room. Some say it was given to the Secret Service. At that moment, the suit was unimportant.

Random bits of detritus made it through the chaos of that day—a typed copy of the itinerary, a stained breakfast program, partial lists of who had tickets to the event, and photographs of the motorcade in front of the Hotel Texas. But the pink suit went missing.

The National Archives in Washington, D.C., houses the Constitution, the Bill of Rights, and also what’s left of that day in Dallas. There’s the white lace-up back brace—the President’s back had become so painful that he couldn’t have sat in the car without it. There’s also his tie, nicked by the bullet, and the shirt that was cut off by the medical team. In a cave somewhere, in an undisclosed location in Kansas, the Archives have also stored the entire contents of Parkland Hospital’s trauma room 1, where he was pronounced dead at one p.m., Central Standard Time.

They also have the pink suit.

It’s never been cleaned.

No one at the Archives seems to know exactly how it got there. It’s currently stored in a climate-controlled vault in area 6W3, although no one can recall it arriving. It may have been mailed, although the package had no postmark. It had been wrapped in plain brown paper. There was no return address. A single-digit postal code was written on the address label, and yet the United States had adopted five-digit zip codes on July 1, 1963. Inside, the suit, the blouse, the handbag, the shoes, and even the stockings were bundled together, along with an unsigned note on the letterhead stationery of her mother. Worn Nov. 22, 1963. That was all it said.

How the mother came to have the suit is still a matter of speculation, but in an audio recording stored in the presidential library, she reveals that she’d kept it in the attic of her Georgetown home. She had Alzheimer’s when she gave the interview. She doesn’t say how she got it, or why it was kept there, or for how long. But she did say that she’d given strict instructions to the maid not to have it cleaned. It was the “last link.” And so she put it in her attic, next to her daughter’s famous wedding dress.

Who sent it to the National Archives instead of the presidential library, and why, is still unknown. When it was finally discovered, the suit was not in a brown bag but in the original box from the dressmaker Chez Ninon.

Chapter One

“[The presidency] was like a film and I had the opportunity to dress the female star.”

—Oleg Cassini

September 1961

In the newspaper, next to the photo of the First Lady in Palm Beach, there was a story about the Greyhound bus that had been firebombed on Mother’s Day. The Attorney General, whom everyone in Inwood just called Bobby, had finished his investigation and now blamed “extremists on both sides.” It was such a shame that the story was next to the photo of the Wife, who was looking so very happy after spending the weekend poolside with her in-laws and children and an assorted tangle of dogs. It just made it all seem sadder. Kate hated to read that this sort of thing was still going on, especially on Mother’s Day. If Patrick Harris’s mother, God rest her soul, hadn’t sponsored her at Chez Ninon, Kate had no idea what she would have done. A magnificent seamstress Peg Harris was. Her son, the butcher, could truss a lovely roast, to

o.

Kate gave the man at the newsstand a dime for two newspapers because she liked the photo of the First Lady so very much, and then put her subway token into the turnstile. While she waited for the A train, she said a prayer for all those people who had been on the Greyhound bus, and their mothers, and her own mother, who had died young, and Patrick Harris’s mother, Peg, who had recently passed, and Mother Church, just to put a good word in. All the way downtown, from Inwood to Columbus Circle, Kate could not stop staring at the photo of that dress. It was quite flattering. The Wife was leaving Florida on Air Force One—smiling, fit, and tan. She was wearing a white scarf and gloves. The neckline of her dress ran right below her collarbone, right where it should be.

Kate had lost track of how many times that neckline had needed adjusting so that it would hit just so. It had been worth it, though. The cut of the dress was remarkable. It hid every flaw—and there were many. Kate thought of the First Lady as “Slight Spinal Sway.” Patrick Harris, the butcher, told her that kind of thinking was an occupational hazard. “I always think of people by what they buy. Mrs. Leary is ‘Pork Loin Joint with Rind.’ ”

Kate, fine boned and pink skinned, always wondered what part of the pig Patrick thought of her as but certainly understood the sentiment—entire families were known to her only by what they wore: fathers and sons in matching suits with the cut of Savile Row, or mothers and daughters with their identical rabbit-trimmed bathrobes. Unless they were extremely famous, appearing in newspapers or magazines, Kate had no idea what they looked like. Chez Ninon had strict rules about mixing. Kate never left the back room. Maeve did the fitting. Kate just followed the marks. She knew everyone’s tucks and pleats but not their faces.

Still. She knew them. More important, she knew who they thought themselves to be. It was Kate’s job to know. As soon as those people were out of diapers, there was a constant need for various wardrobes for skiing, horseback riding, private school, and spring holiday in Paris—along with Having Lunch with Mummy at the Four Seasons dresses and Meeting Other Children in Central Park Harris tweeds.

Stitch by stitch, hour by hour, Kate imagined every formal dinner, every exotic holiday, and every debutante ball as if she lived them herself. It was the only way to get the clothes right. She needed to understand how long a cape could be without being too long and thereby unfashionable, or what type of lining a Belgian-lace suit needed so it would stay cool and yet not wrinkle in the Caribbean sun. Kate was just thirty-two, and yet so many years of her life had already been spent hunched over one fabric or another, her focus unwavering. A simple dress could take a hundred hours to make. A beaded gown could run over a thousand, sometimes two. But she never met the clients.

Outside the Columbus Circle station, the morning seemed vain and preening. The endless green of Central Park was edged with the gilt of fall. Swarms of fat yellow cabs circled. As Kate passed the long row of livery carriages getting ready for the day, the drivers placed garlands of plastic flowers over the horse’s heads. The beasts were stoic, as if resigned to their lot in life. Every now and then, there’d be a shake of the head or a snort. But they never bayed or bucked. The blinders they wore narrowed their world.

Kate loved horses ever since she was a child. On the Great Island, in Cobh, on the coastline of County Cork, wild horses lived along the beach. If you were gentle, and had an apple in your hand, sometimes they’d let you get close enough to lasso them. If you were careful, you could slip onto their backs and they would gallop full bore along the brilliant sapphire sea and you could lean into them, listening to the beat of their untamed hearts. But you had to be gentle and very careful. And Kate was both.

City horses were very different. They wore hats and walked round and round all day. Of course, so did Kate.

Clip, clop, she thought.

From the street, Chez Ninon was nondescript at best. The dress shop was a series of second-floor windows in a Park Avenue office building that could be easily overlooked—and that was the point. Discretion was essential to their business. Most of Chez Ninon’s clients were part of the Blue Book society, the old-money crowd. The owners, Sophie Shonnard and Nona Park, were Blue Book, too. They were also glorious crooks.

Kate had been told that Miss Sophie and Miss Nona’s evolution into the life of artistic larceny was a gradual process, a matter of supply and demand. For nearly forty years, “the Ladies,” as they called themselves, had run a custom shop in Bonwit Teller that produced only original designs. But as time went on, more of their fellow Blue Book friends wanted French fashions without the French price tag. And so, in the spirit of friendship and a healthy bottom line, every season Miss Sophie and Miss Nona flew to Paris to pilfer the very best designs from the finest runway shows.

Chanel, Lanvin, Nina Ricci, Cardin, Givenchy, and Balenciaga—the Ladies would carefully watch each collection and then run to the nearest sidewalk café to sketch the garments from memory. Once back in New York, they would create fifty designs or more but make only four copies of each. For special clients, like the First Lady, they would offer exclusive copies of the pieces they knew would be of interest, with exclusive price tags to match. No matter what couture house the Ladies had stolen their designs from, they would put their own label on the finished clothes. Chez Ninon. New York, Paris. When a collection was ready, the Ladies would pop champagne and open their doors at precisely three p.m., from Tuesday to Thursday. Everything was sold on a first-come, first-served basis. By invitation only.

Every season, the Chambre Syndicale de la Haute Couture et du Prêt-à-Porter forced Chez Ninon to pay a “caution fee” to the French designers. The Ladies always pronounced it cow-see-on—the fee was so exorbitant, they could pronounce it any way they pleased. If they didn’t pay, they couldn’t attend the runway shows. But they always paid. There was no way to ban them.

Miss Nona was more than seventy years old, but how much more was difficult to determine. She was always red-carpet ready, dressed in the originals that she so shamelessly copied, and demanding front row seats at all the best runway shows. Macy’s, Marshall Field’s, Ohrbach’s, even Bonwit Teller—if Nona wanted a buyer’s seat she’d take it. She had sharp elbows and the air of a deposed duchess; no one dared refuse her. Her partner, Sophie, only slightly younger, tagged along behind her, apologizing and wielding her Southern charm with the precision of a surgeon. The Ladies would not tolerate being ignored or silenced. They were always exacting and always in the way.

“Wonderful and pixilated,” an editor at Vogue once called them. Carmel Snow, the editor in chief of Harper’s Bazaar, considered them the most “discerning American buyers of Parisian fashion.” Miss Nona was even featured in a nail polish ad. They were charming pirates, but they were pirates nonetheless.

Luckily for Kate, they never came in until after ten.

Morning light streamed in through the large windows. It was early. The sewing machines in the Ready-to-Wear Department were, thankfully, quiet. Black-and-gold enameled beasts—they still had treadles. The machines were noisy and burned the girls’ arms and hands if they overheated—and they always overheated. The Ready-to-Wear girls were the mice of the back room, pumping the treadles of their machines like the pedals on a pipe organ. Laughing and gossiping, they hummed with life. Most wore their hair in curlers or shaped into spit curls that were taped into place. They were young and always ready for a night out. Their quick eyes and even quicker hands stitched without care. Kate never understood why a seamstress with as much talent as Peg Harris had spent her days running off dozens of dresses on a machine, but Peg clearly had loved doing it. “Clothing the masses is noble work,” she’d tell anyone who asked. Kate agreed, but she would certainly rather dress the First Lady.

She tossed the newspapers on her desk and put the kettle on for tea. She could hear Mr. Charles on the telephone behind the closed door of his office. Noel Charles was the in-house designer at Chez Ninon and Kate’s direct supervisor. Silver haired and impeccable, he was manicur

ed down to his buffed fingernails. He had an accent that was somewhat European. He always spoke of Belgian roots, but to Kate he sounded neither French nor Dutch. He had a vague Continental air; his accent was chameleon-like and shifted depending on whom he was speaking to.

He hoped to open his own shop soon and talked of taking Kate with him, as a partner. It was such a grand scheme—it didn’t matter if it was truly possible or not. Kate just liked sitting in the quiet workroom with Mr. Charles early in the morning. They would have tea and talk about important things, like current events. It was civilized.

The kettle whistle blew. There was some Barry’s Gold Blend in the cupboard, which Kate had found in a specialty shop downtown. She’d paid a dear price for it, and it was stale, but stale Barry’s was better than A&P tea anytime.

She carefully trimmed the photos of the First Lady from the newspapers that she’d bought at the subway station. One copy was for her scrapbook and the other she tucked into her weekly letter to her father, along with half of her salary, twenty-six dollars. The Old Man never mentioned the clippings at all, and so she never did, but it was interesting to Kate to see if the gossip columnists recognized that the Dior gown was not really a Dior at all. And there was something so wonderful about seeing the way a gown was worn—the way the shoulders turned, the head tilted, or the iridescent beads caught the light. Even after all this time, seeing her own work worn still thrilled her.

Fashion is the art of the possible—Kate was quite fond of saying that, but it was true. With a needle and thread in her hand, anything was possible, especially when it came to the First Lady, because Kate’s sister, Maggie Quinn, and the Wife were exactly the same size. Kate couldn’t help herself. On a rather regular basis, she turned her own sister into a “Little J,” as everybody in the neighborhood called her. There was no harm done. The muslin patterns were often tossed away, so Kate just plucked them out of the trash. Her sister was a little younger than the Wife, but their coloring was very similar. And they were both Sunday-china beautiful. Kate always tried to be respectful about it. She never made the exact same outfit if she could help it. She’d usually try a different fabric entirely, although sometimes it would be a similar color. And she never had the hats made up—even though Schwinn, one of the boys at the shop, who always rode a bike to work, was a very fine milliner.

The Pink Suit: A Novel

The Pink Suit: A Novel